From The Washington Post…

--------------------------------------

Athletes Black and Blind

By Michelle Singletary

Are black athletes wasting their considerable wealth?

Sportswriter William C. Rhoden thinks so.

Considering that February is Black History Month, I thought it was a perfect time to discuss whether black athletes are failing to use their money and influence to significantly tackle the social ills -- such as poverty and unemployment -- that are still plaguing the black community.

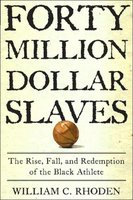

Rhoden adds a powerful voice to this debate. It’s why I’ve chosen his book “Forty Million Dollar Slaves: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Black Athlete” (Crown, $23.95) for the February Color of Money Book Club.

Rhoden’s book raises provocative questions about wealth and responsibility. If wealthy black athletes donate money to charity, are they obligated to donate their personal time as well? If they donate their time, are they obligated to become spokesmen for a political or social cause as well? How much is enough? And who decides? Such questions are particularly important to ask of those among us who have been blessed with considerable economic resources.

Rhoden, who is African American, has been a sportswriter for the New York Times since 1983. He’s written the “Sports of the Times” column for more than a decade. He’s been up close and personal with the best-paid black athletes in this country. In his new book, Rhoden gives a much needed slap-down to wealthy, spoiled and socially unconscious African American professional sports figures.

Rhoden acknowledges that calling millionaire athletes slaves would stir up controversy. Even so, he says he uses that term because these players’ professional lives are controlled by white team owners.

“To the general public, athletes have achieved the Promised Land,” he writes. “The inference never far from the surface is that they should be grateful -- more grateful than their white peers -- for the money they make.”

Rhoden’s point is timely, considering all the media attention on the fact that for the first time two black men are head coaches in the Super Bowl. However, what I find fascinating about this book is that Rhoden doesn’t just criticize white sports-team owners. He spends far more time criticizing black athletes for not being more vocal about social issues important to the community.

Perhaps it’s not fair to swipe at them without a full analysis of all their personal charitable contributions, but I was nodding in agreement at Rhoden’s assessment of the modern black athlete.

We shouldn’t strive to be like Mike, according to Rhoden. Because what exactly has Michael Jordan stood up for off the basketball court?

Well, little more than making money and hawking products, Rhoden argues. Jordan has again and again chosen commercialism over important community and political advocacy, he says.

Jordan takes a great many hard shots from Rhoden, who says today’s black athletes like Jordan “have abdicated their responsibility to the community with an apathy that borders on treason.”

“When the face of black sports is Kobe Bryant or Mike Tyson or even a raging capitalist like Bob Johnson, it’s clear that the sense of a larger mission has collapsed,” he writes. “More than politicians or clergy, contemporary black athletes have unfettered access to young minds, even when at times they seem to have lost their own. They exercise phenomenal influence on styles and tastes, but their reach could potentially extend so much wider, and deeper.”

For example, Rhoden feels black athletes did not do enough in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina destroyed thousands of homes and displaced thousands of families, many of them black. While some athletes did donate their time and money, Rhoden notes that no one really stepped up to “galvanize the collective power of African-American professional athletes to create a more far-reaching initiative,” he says.

Where was the teamwork many of these athletes display in their sports? Rhoden asked.

But as his book title suggests, these players can redeem themselves. Rhoden proposes creating a national organization of professional black athletes to use their wealth and influence to improve the economic condition of many black folks who can’t afford to even go to their games.

I agree with Rhoden: To whom much is given, much is required.

1 comment:

Agree totally Jive.

There are so many non-controversial projects these guys can really make a difference with.

First and foremost is the whole notion as voiced by Cosby and Sharpton (go figure) that too many young Blacks equate doing well in school with being white. Given that most of these athletes are college grads (and some, especially NBA stars, from top schools like Duke & Stanford) that seems a particularly ripe area.

Post a Comment