From The Chicago Tribune…

--------------------------------------------

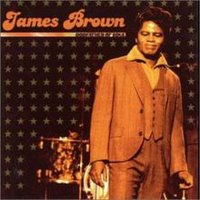

Godfather of soul, and of our goal

By Clarence Page

WASHINGTON -- Can James Brown really be gone? Are we sure? After all, no one could stage a false exit better than the Godfather of Soul.

He’d be singing “Please, Please, Please” down on one knee at the foot of the stage, his face gleaming with sweat, his pompadour gleaming with pomade, after two hours of sweet pulse-pounding soul stirrings. Then his dapper assistant would appear and drape a bright satin cape over Brown’s shoulders and Soul Brother No. 1 would slowly stand up and turn around slowly and step rhythmically offstage as the band and backup singers, moaned “Please, please don’t go-oh-oh … “ and … the … crowd … would … go … wild!

And Brown would stop, shake off the cape, which the dapper aide would catch in the nick of time, and dance back to center stage for an encore! And another! And another!

It was pure cornball show biz, but we, the James Brown Baby Boomers, loved it because Brown did it with so much, ah, yes, soul!

In fact, he defined “soul” in the 1960s and forevermore as much as Sam Cooke or Aretha Franklin or Ray Charles or the Supremes or Jackie Wilson or Marvin Gaye or anybody else in the rhythm-and-blues pantheon. His 1962 “Live at the Apollo” hit album set the mood for countless “blue-light” parties in our parents’ basements. His eye-defying, quick-shuffling, rubber-legged dance moves were widely imitated but never quite duplicated. Others like Joe Tex or Jackie Wilson or Al Green might be able to drop the mike, spin around, drop into a split and catch the mike before it hit the stage floor, but never with the same level of style, flair and all-out screaming passion as Brown.

Ever wonder where Rev. Al Sharpton found his exotic hairstyles? Blame Brown.

J.B. befriended Sharpton, then a prodigious teen preacher and youth leader who became Brown’s road manager in the 1970s. When Sharpton married show business and civil rights activism, he learned from the master.

Ever wonder why Mick Jagger started dancing like a madman on stage? Blame Brown.

As a singer, Jagger was a remarkably calm-looking chap until the Rolling Stones were booked to follow Brown in the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium in 1965. As “The T.A.M.I. Show” (Teen-Age Music International) video documentary reveals, “The Hardest Working Man in Show Business” whipped those California kids into such a frenzy that a nervous young Jagger decided to explode onto the stage with an improvised chicken walk dance that soon became his trademark. Jagger has hardly stopped moving onstage since.

And after surviving the Motown wave and the British invasion, Brown proceeded not only to “go political,” as many performers did in the 1960s, but write the anthem for a new sociopolitical consciousness: “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud.” No one drove the nail into the coffins of “colored” and “Negro” as acceptable labels as much as Brown’s song did.

Yet, as music and message, I prefer the less known anthem with a mouthful of a title that says it all: “I Don’t Want Nobody to Give Me Nothing (Open Up the Door, I’ll Get It Myself).”

Musically, the song’s compelling beat displays to full effect Brown’s distinctive emphasis on “the ones” (the one and the three, instead of the two and the four) in his rhythms. Its message offers an important response to the many people who were asking in the midst of urban riots and a rising black power movement in the late 1960s, “What do black people want?”

If Brown’s answer is what it sounds like in his songs, “We want equal opportunity, not guaranteed results,” it should come as no surprise that he endorsed Richard M. Nixon in 1972 for president. After all, it was Nixon, not John F. Kennedy or Lyndon B. Johnson, who actually signed the first affirmative action executive order into law.

Looking back, it is easier to appreciate the message Brown was trying to give. “Black power” rose in 1966 in the wake of the civil rights movement as a slogan in desperate search of a program. Brown, a 7th-grade dropout, suddenly became the least academic but most influential voice to give a little intellectual meat to the new movement.

As an impressionable student, I was changed forever by Brown’s recounting in an interview in the late 1960s about his own struggles against childhood poverty. “I used to shine shoes on the front steps of an Augusta, Ga., radio station,” he said. “Now I own that radio station.” So could we all, he was telling our generation, if we took full advantage of the doors that were opening to us.

Unfortunately, Brown took great advantage of those open doors only to lead a life of maddening swings between wealth and ruin, artistic genius and spouse abuse, amazing fitness and drug abuse. Yet he kept coming back for encores and honors. The curtain has come down on his turbulent life. This time his exit is for real. But we still have his music, his memories and his messages, still taking encores for many years to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment